Quite simply, It’s what Persianate artists do

Picture Books of The Mongols

A turbaned figure is perched upon a rock. His long-braided hair falls forward over his chest, the ends of which are tucked beneath his knee, clasped firmly within his arms. He looks ahead and down slightly, avoiding eye contact with a brilliant, winged creature standing a few feet to his left. The unnervingly tall humanoid arches forward and gesticulates with a single finger towards the man deep in contemplation. This is the scene depicted in the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh of Rashid al-Din Hamadan, one of many that includes the Prophet Muhammad, unveiled and presented matter of fact. In the above scene, the Prophet is receiving revelation from the angel Gabriel. It is perhaps, as Shahab Ahmed argues, the foundational hermeneutical axis upon which everything “Islamic” turns. That is to say, the image is reverential, if not outright devotional.

This was my first visual introduction to Muhammed as a child, and it is the image that is conjured in my head when his name is invoked. I had received a fairly generic “Visual Introduction to Islam” book from a family friend. It got me hooked, not so much on the religion or tradition but a feeling. The Silk Road, Bactrian camels carrying heavy loads and heavier ideas, dazzling Persian miniatures, youths and heroes, Asiatic steppe peoples, a renaissance happening somewhere in between the barren steppes of Central Asia. It made a powerful impression on me that I’ve never quite shaken.

And in amongst all of this was the image of Muhammed receiving revelation from the angel Gabriel. The images are vertical and executed in wash, typical of early Ilkhanid works. Although not as brilliant as miniatures of the coming centuries, it betrays elements that convey the world of the Persianate imagination. The backgrounds twist and curve, often towering well over the figures. They reveal a sense of unsettling calm amongst the often-otherworldly happenings. But these images were also made for a purpose, legitimating Mongol rule over Iran and presenting Islam and Persian culture in a way that would resonate with the new elites. Art historian Christiane Gruber argues that depictions in this period stress Muhammed’s role as a divinely ordained leader, drawing parallels with Mongol concepts of heavenly mandated kingship.

Images like these reveal the ambiguity of Mongol religion in Iran. Straddling the worlds of Buddhism, Islam and indigenous steppe practices, the three would occupy the same space for a time with often intriguing results. Tegüder Ahmad (1281–84) marked the first convert to Islam but was succeeded by a devout Buddhist. According to Gruber, he was almost certainly converted to Sunnism by a mystic, Kamal Al Din Al Rahman. His Buddhist successor, Arghūn, likewise welcomed countless Sufis to court and even made pilgrimages to their tombs. These Sufis were by and large “orthodox” Sunni Muslims, but the wandering Qalandars (or adjacent groups) were certainly no strangers to Mongol patronage. It is said Ahmad himself was partial to the tradition. The enigmatic Barak Baba who appeared in Damascus with the Ikhanid standard had earlier received patronage from the first Ilkhan Hulegu, also a devout Buddhist.

I’ve reflected on how my exposure to Islam has some unexpected parallels to that of a Mongol or Turkic newcomer, enamored with his newly adopted Persian culture. Alone in my room, reading a heavy tome embellished with miniatures. Scenes of heroic saints traversing worlds in between worlds play out in my head. And like those Mongols, I almost certainly benefited from an elite separation vis-a-vis Islam as it may be ordinarily practiced in many other settings. I never had to step foot in a Mosque or interact with a Muslim community and deal with the kind of narrow-minded bigotry and banal thinking that permeates these spaces of conformity. Instead, against all odds, I received from a kind of pre-modern exposure to religion, one which isn’t entirely reducible to the minutia of jurisprudence. The Seljuk rulers who rode to war against the Byzantines, mace in hand while reciting the Shahnameh, glorifying Zoroastrian Kings of old were also unrepentant Sunni Muslims. It is as much Islam as anything else.

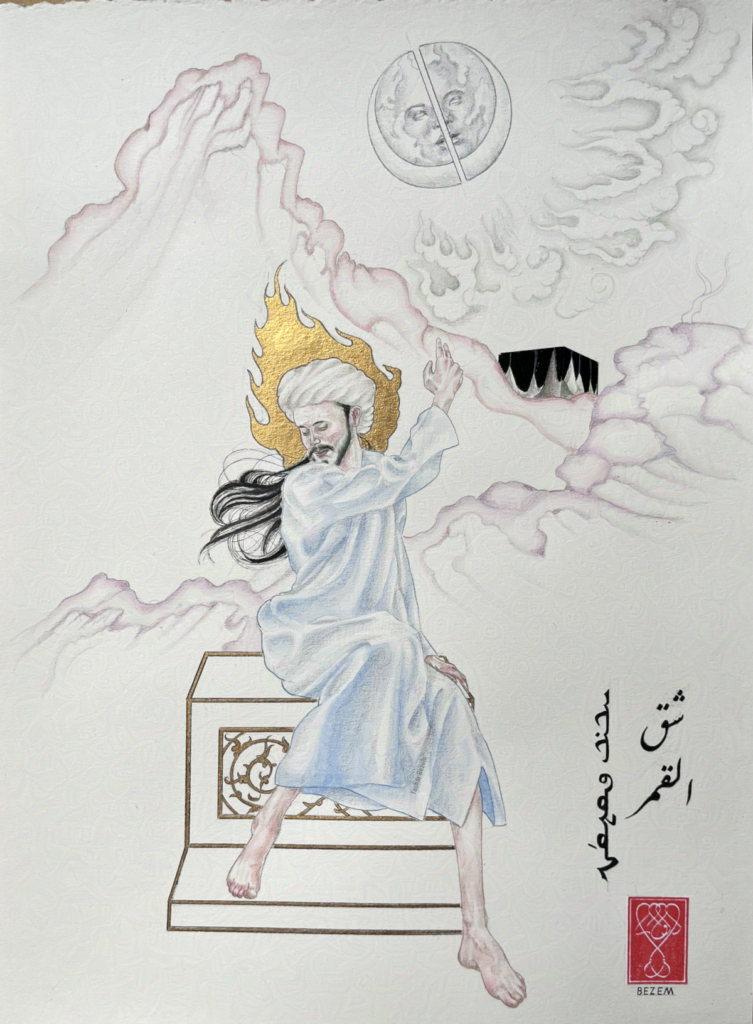

The Splitting of The Moon

And so, my painting you see here are an instantiation of these ideas in my head. Much as the miniatures of the Ilkhanid period reflected the tumultuous state of affairs of the Mongol period (as well as the new possibilities it afforded), my drawings evoke a similar set of confluences taking place in a more personal level. The Asiatic influence is likewise present but more informed by the Japanophilia of Scottish Art Nouveau (I do live in Glasgow after all). Muhammed’s hair is in Sumi-e Ink, and I chose to paint it in a way that evokes Ukiyo-e woodcuts. The background is, much like the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh, executed in wash but more in the style of later Safavid miniatures. The clouds part behind the Ka’aba and reveal a face in the moon, split cleanly in the middle.

The scene I chose to depict here is one of the more well-known miracles performed by the Prophet and a favourite among Persian miniaturists, the “Splitting of the Moon”. The Prophet Muhammad gestures in the company of disbelieving Quraish tribesmen and appears to cleave the moon in two. Annemarie Schimmel recalls the Persian poet Sana’i who symbolically equates Muhammad with the Sun (as is common in mystical literature) remarking that it was appropriate that the Sun should split the Moon. Another Sufi interpretation would be acknowledging having been self-annihilated by the nur-ı Muhammed (the Muhammedan light), the primordial source of all reality.

Eagle-eyed readers may notice the inclusion of a strange, non-Arabic script included in the bottom right of the image. These are my renditions of Old Uyghur, an Aramaic based script adopted by the Turkic Uyghurs of the 700s in the Tarim Basin before flourishing in Central Asia in the 15th century. This continued to be used by the newly arrived Turkic peoples of Anatolia along with the Mongols who had used it as the basis for their own alphabet.My reason for using it here was to stress the enigmatic aura of the world from which these images emerge. The liminal possibilities made present by the encounters (both positive and otherwise) of radically different groups, outside the gaze and control of totalising (and totalitarian) religious systems.

To share a preview on my musings on the matter from my artbook on Anatolian Sufism:

“This isn’t a world that one would immediately recognise coming forward with many of the unchallenged assumptions we may have of certain groups of people and their apparent religious and ethnic affiliation as it exists today. It is this uneasiness that I have strived to convey in these drawings. It is a testament to the strange beauty made possible when the genius of the human spirit is untethered to banality. When the confluence of peoples, their history and traditions come to a crossroad and all is, however briefly, thrown up in the air, freeing those daring enough to pick up the pieces where they fall and make radically new but remarkably timeless realisations.”